Beyond Checklists: Standing Orders for Health Care

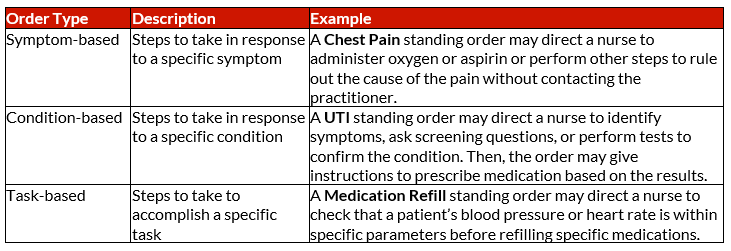

A standing order is a list of steps a doctor has pre-authorized non-practitioners to take in order to complete specific medical tasks. Standing orders are intended to streamline medical care and often include blanket instructions to accomplish this. For example:

Stop using standing orders

Standing orders are often used in hospitals and nursing homes to deliver routine preventative care services, but nothing is routine in corrections. Standing orders may lead to missed illnesses and inappropriate care if a staff member is “checking boxes” and not individually evaluating detainees.

That said, it is important that a professional with the appropriate knowledge base addresses serious health issues. In jail, it is not just the health care team who carry out medical orders – officers are often asked to follow practitioner orders.

Especially in jails that do not have 24/7 on-site nursing, officers may be the first people to be made aware of detainee health concerns. They may not have the knowledge and training to triage health concerns that nurses in a hospital do.

It is not in a nurse’s scope to make medical decisions, diagnose medical problems, or determine that a patient is not ill.¹ For example, a standing order that asks a nurse to identify a checklist of specific symptoms may lead to a missed illness if a detainee has a symptom outside of those listed in the order. Stop using standing orders.

Individualize well visits

Detainees in the jail environment have diverse health histories and often experience comorbidities. Standing orders do not account for continuity of care post-release, or the unique circumstances of incarcerated patients. Detainees have a constitutional right to care, which means not providing access to the appropriate care could be a civil rights violation.

Each detainee health issue should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, and orders should be verbalized or confirmed by the practitioner. If medical is not on-site, this may mean a call to the practitioner is appropriate.

· Officers should document detainee health issues and call the practitioner when they arise and medical is not on-site. Click here for a sample documentation form.

· Nurses should contact the practitioner with their concerns or the results of an examination to receive individualized orders before attempting to treat a detainee.

· Practitioners should issue orders specific to an individual detainee’s situation. Practitioners can give parameters and conditions for the order but should not issue blanket orders to treat.

It is okay to ask for clarification or additional instructions when receiving orders from a practitioner. Remember, you are not arguing; you are looking out for the detainee, the practitioner, and yourself. Individualize well visits.

For more information, please contact training@sparktraining.us.

1. National Council of State Board of Nursing (2021). “NCSBN Model Rules.” NCSBN, https://www.ncsbn.org/papers/ncsbn-model-rules.

Disclaimer

All materials have been prepared for general information purposes only. The information presented should be treated as guidelines, not rules. The information presented is not intended to establish a standard of medical care and is not a substitute for common sense. The information presented is not legal advice, is not to be acted on as such, may not be current, and is subject to change without notice. Each situation should be addressed on a case-by-case basis. When in doubt, send them out!®