Combat cocktails and corrections don’t mix

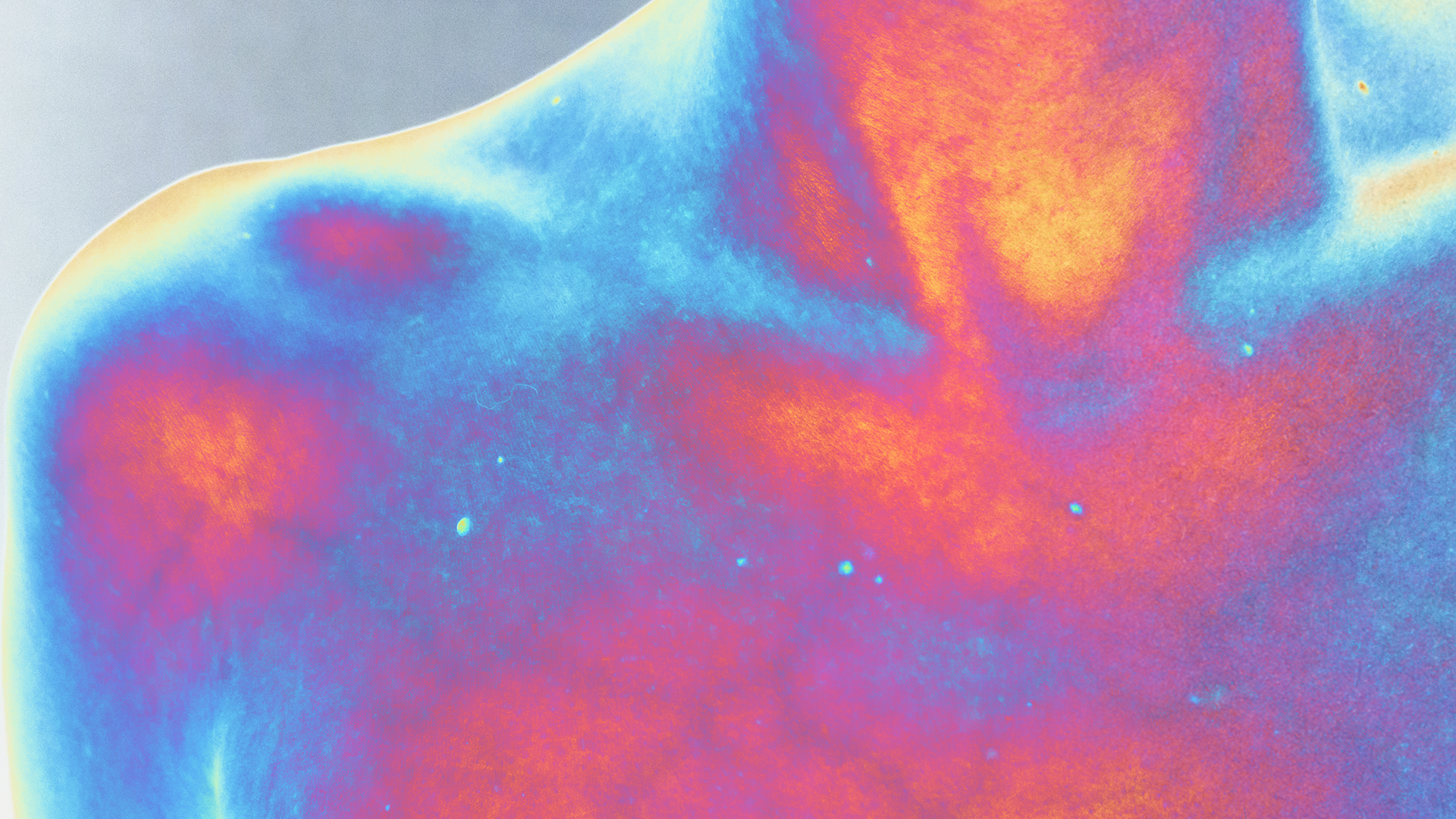

Daniel is a veteran who was prescribed an antidepressant on his return to the U.S. The drug caused Daniel to feel tired and emotionally numb. When he told his doctor, he was prescribed a stimulant to counteract the effects. He has tried to stop taking the medications, but experiences extreme withdrawal symptoms each time. Now, Daniel is being booked into jail and the site doctor has to determine whether to keep prescribing the medications or to come up with an alternative treatment plan.

85% of veterans receiving mental health or substance use treatment carry at least one criminal charge.¹ It is not uncommon for incarcerated veterans to be prescribed a variety of medications to treat issues like PTSD and depression, called a “combat cocktail.” While the combat cocktail is unfortunately rampant in veteran populations, any individual can be booked into jail with multiple prescriptions, which can raise health concerns in correctional settings.

Provide counseling

Medications without therapy fail to treat the root cause of trauma and can end up doing more damage to the body and mind than good. Unfortunately, most detainees receive medications, not therapy, to treat mental health issues in jail.² The approach of throwing medication at problems has been criticized in general, but this practice brings a unique set of challenges in a correctional setting. Many medications have a high potential to be diverted or misused in the jail, and studies show that detainees struggle to continue taking prescribed medications post-release—either due to lack of health care access, money, or barriers to medication management and support.³,⁴

It is recommended to provide counseling and therapy to individuals with mental health issues in jail. If your jail does not have an on-site qualified mental health professional (QMHP), telehealth options can help provide care to those who need it. QMHPs, discharge planners, and medical personnel should collaborate to ensure that therapeutic treatments are considered appropriately before resorting to prescriptions. Use telemental health options to provide counseling for detainees struggling with mental health issues.

Don’t stop SSRIs cold turkey

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) are antidepressants that have been associated with an increased risk of suicidality, particularly when starting, stopping, or changing doses.⁵,⁶ Individuals who enter jail with SSRI prescriptions should have access to close monitoring, ongoing therapy, and continuity of care post-release to avoid bad symptoms and withdrawal. If an SSRI needs to be deprescribed, the detainee should be slowly weaned off the medication over a long period of time. The average jail stay is generally NOT enough time to completely wean off an SSRI. Careful planning and communication with community providers is paramount when determining prescription changes for SSRIs to avoid withdrawal. Initiate withdrawal procedures for detainees who stop taking SSRIs. Do not stop SSRIs cold turkey.

For more information, please contact training@sparktraining.us.

Timko, C., Nash, A., Owens, M. D., Taylor, E., & Finlay, A. K. (2020). Systematic Review of Criminal and Legal Involvement After Substance Use and Mental Health Treatment Among Veterans: Building Toward Needed Research. Substance abuse: Research and Treatment, 14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178221819901281

Maruschak, L. et al. (2021). Indicators of Mental Health Problems Reported by Prisoners. Bureau of Justice Statistics, https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/document/imhprpspi16st.pdf

Browne, C. (2022). Continuity of Mental Health Care During the Transition from Prison to the Community Following Brief Periods of Imprisonment. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.934837

Magura, S. et al. (2009). Buprenorphine and Methadone maintenance in Jail and Post-Release: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 99(1-3). 222-230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.006

Nischal, A. et al. (2012). Suicide and Antidepressants: What Current Evidence Indicates. Mens Sana Monographs, 10(1), 33-44. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1229.87287

Reeves, R. & Ladner, M. (2010). Antidepressant-Induced Suicidality: An Update. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics, 16(4), 227-234. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00160.x

Disclaimer

All materials have been prepared for general information purposes only. The information presented should be treated as guidelines, not rules. The information presented is not intended to establish a standard of medical care and is not a substitute for common sense. The information presented is not legal advice, is not to be acted on as such, may not be current, and is subject to change without notice. Each situation should be addressed on a case-by-case basis. When in doubt, send them out!®