Fix Jail Food, Fix Behavior

Kevin, a 36-year-old detainee with a history of erratic and aggressive behavior, is known for outbursts, fights, and constant rule violations. Officers routinely prepare for physical intervention. After a behavioral health consultation, medical staff recommend a regimen that includes vitamin D and omega-3 supplements. Within two weeks, officers note a sharp decline in incident reports. Kevin’s behavior stabilizes. He begins attending programming. He eats better. Fewer outbursts. Fewer restraints.

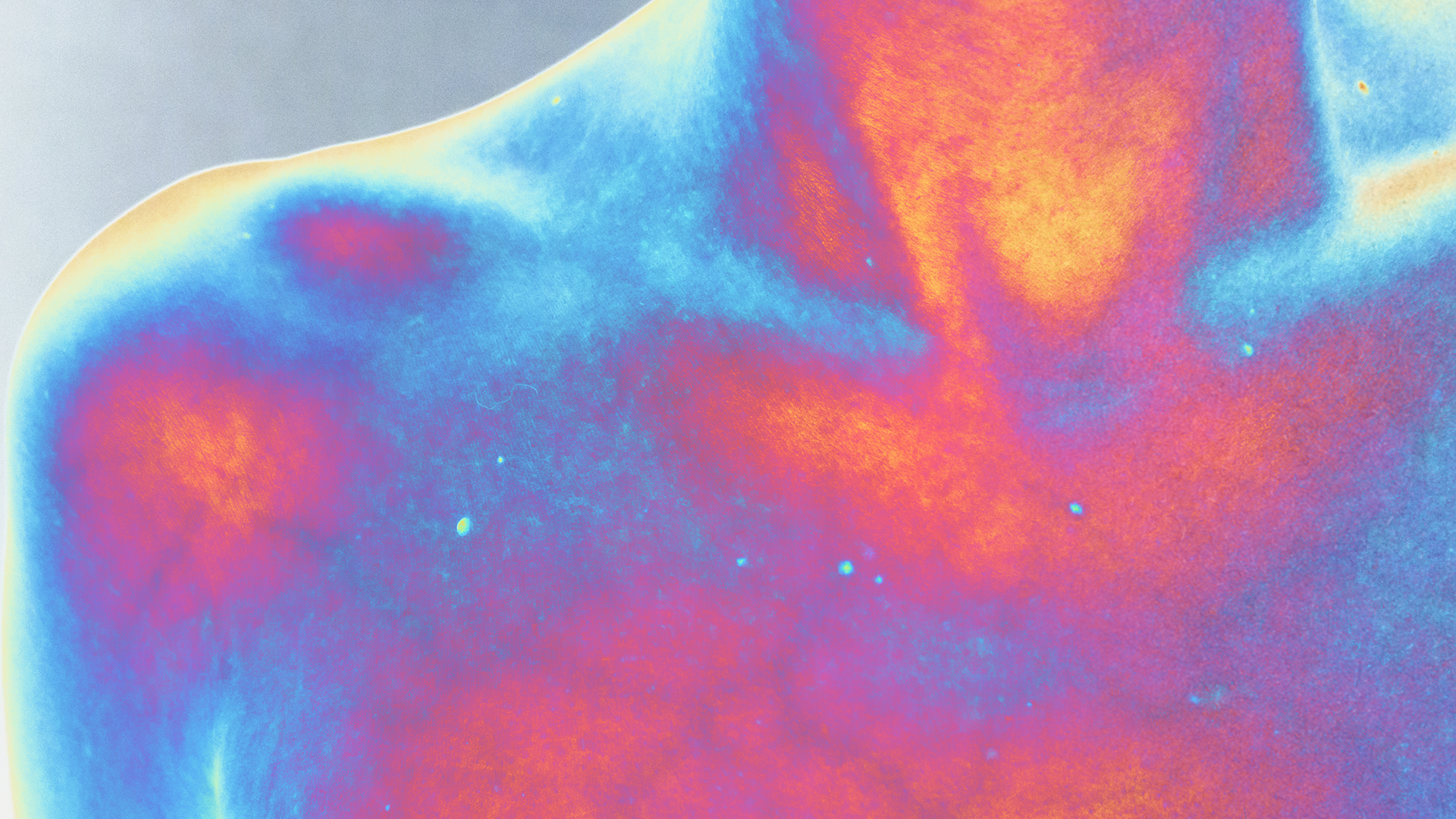

Facilities often overlook the role of diet in behavior and chronic illness. Ultra-processed jail food is linked to obesity, hypertension, and diabetes. It also impacts mental health. Emerging evidence shows that improving nutrition through clean water, minimally processed meals, and nutritional supplements can reduce aggression and improve outcomes for both detainees and staff.

Install clean water systems

Clean, filtered drinking water is a basic human right. Yet, many jails struggle with poor water quality due to aging infrastructure and contamination. Legionella outbreaks from contaminated water in jails are a frequent occurrence.

Install a centralized reverse osmosis (RO) filtration system paired with vandal-resistant stainless-steel stations. RO systems remove up to 99% of contaminants commonly found in U.S. correctional water supplies.

They’re cost-effective:

Serve large populations with low per-gallon cost

Basic maintenance (filters every 6–12 months; membranes every 1–3 years)

Reduce lawsuits related to waterborne illness or contamination

Tamper-proof stations with heavy-gauge construction reduce vandalism and extend system life. One central unit can supply water to multiple cell blocks, lowering long-term costs and simplifying upkeep.

Grants from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) and state agencies may be available to help fund installation. Water isn’t optional. It impacts physical health, mental clarity, and even behavior. Install clean water systems.

Ask vendors for Nova-compliant meals

Ultra-processed meals make up the bulk of jail menus. These foods—often shelf-stable, high in sodium, sugar, and additives—are linked to obesity, diabetes, and behavioral issues.

Ask your food vendor to comply with the Nova Food Classification System, a global standard for rating food processing levels. Focus on:

Group 1: Unprocessed/minimally processed foods

· fruits, vegetables, grains, eggs, legumes

Group 3: Simply processed foods

· canned beans, cheese, bread

Limit Group 4: Ultra-processed items

· frozen entrées, packaged snacks, sugary drinks

Aim for a diet consisting of 2,000–2,500 kcal per day based on age, sex, and activity level. Prioritize fiber (aim for 25–30 g per day), whole proteins, and hydration. Limit sodium to 2,300 mg or less per day. Track health metrics like weight and blood pressure to evaluate the health impacts of these changes. Improved nutrition means fewer sick calls, fewer chronic complications, and lower healthcare costs:

Up to $6,299 per patient per year in avoided medical costs

10–20% reduction in food waste

Fewer behavioral issues linked to poor diet

Meal quality matters. Ask vendors for NOVA-compliant meals.

Add core nutritional supplements

Correctional diets often lack key nutrients. Add these seven core supplements to improve physical and mental health outcomes.

Vitamin D – Fights depression and supports immunity. Inmates rarely get sun.

Omega-3s – Reduces aggression, inflammation, and supports brain health

Vitamin C – Helps with immunity and stress recovery.

Magnesium – Improves sleep and reduces stress.

Probiotics – Affects gut health, mood, and immune balance.

Supplements are low-cost and high-impact. Behavior improves when the body has what it needs. Staff health and happiness improves when inmates are more emotionally stable. Work with the medical and behavioral health teams at your jail to determine which supplements are clinically indicated. Add core nutritional supplements.

For more information, please contact training@sparktraining.us.

1. Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. (2020). Southwestern correctional facilities’ drinking water puts inmate health at risk. https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/news/southwestern-correctional-facilities-drinking-water-puts-inmate-health-risk

2. Dannenberg, J. (2007). Prison drinking water and wastewater pollution threaten environmental safety nationwide. Prison Legal News. https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/2007/nov/15/prison-drinking-water-and-wastewater-pollution-threaten-environmental-safety-nationwide/

3. Deng, S. et al. (2025). Estimated impact of medically tailored meals on health care use and expenditures in 50 US states. Health Affairs, 40(4). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2024.01307

4. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2015). Guidelines on the collection of information on food processing through food consumption surveys. https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/b8033ea6-184e-4eca-a7a2-8123e2c4103f

5. Kaivac Clean Academy. (n.d.). Guide to cleaning correctional facilities. https://kaivac.com/clean-academy/guide-to-cleaning-correctional-facilities

6. Mommaerts, K. et al. (2023). Nutrition availability for those incarcerated in jail: Implications for mental health. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 19(3), 350–362. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPH-02-2022-0009

7. Monteiro, C. et al. (2018). The UN decade of nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Public Health Nutrition, 21(1), 5-17. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980017000234

8. National Commission on Correctional Health Care. (2023). Nutritional wellness in correctional settings. https://www.ncchc.org/position-statements/nutritional-wellness-in-correctional-settings-2023/

9. National Institute of Medicine, (2006). Dietary reference intakes.

10. National Park Service. (n.d.). Two ways to purify water. https://www.nps.gov/articles/2wayspurifywater.htm

11. Nigra A. & Navas-Acien, A. (2020). Arsenic in U.S. correctional facility drinking water, 2006–2011. Environmental Research, 188, 109768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.109768

12. Prescott, S. et al. (2024). Crime and nourishment: A narrative review examining ultra-processed foods, brain, and behavior. Dietetics, 3(3), 318-345. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics3030025

13. Prescott, S. et al. (2024). Nutritional criminology: why the emerging research on ultra-processed food matters to health and justice. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(2), 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21020120

U.S. Department of Agriculture & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary guidelines for Americans 2020-2025. DGA. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/resources/2020-2025-dietary-guidelines-online-materials

15. Wang, L. (2022). Prisons are a daily environmental injustice. Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2022/04/20/environmental_injustice/

16. Zaalberg, A. (2010). Effects of nutritional supplements on aggression, rule-breaking, and psychopathology among young adult prisoners. Aggressive Behavior, 36(2), 117-126. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20335

Disclaimer

All materials have been prepared for general information purposes only. The information presented should be treated as guidelines, not rules. The information presented is not intended to establish a standard of medical care and is not a substitute for common sense. The information presented is not legal advice, is not to be acted on as such, may not be current, and is subject to change without notice. Each situation should be addressed on a case-by-case basis. When in doubt, send them out!®